如何在 Go 中编写防弹代码:一个针对不会失败的服务器的工作流

From time to time you may find yourself facing a daunting task: building a server that really isn’t allowed to fail, a project where the cost of error is extraordinarily high. What is the methodology for approaching such a task?

Does your server really need to be bulletproof?

Before diving into this excessive workflow, you should ask yourself — does my server really need to be bulletproof? There’s a lot of overhead involved in preparing for the worst, and it’s not always worth it.

If the cost of error isn’t extraordinarily high, a perfectly valid approach is to make a reasonable best effort for things to work, and if your server breaks, just deal with it. Monitoring tools today and modern workflows of continuous delivery allow us to spot problems in production quickly and fix them almost immediately. For many cases, this is good enough.

In the project I’m working on today, it isn’t. I’m working on implementing a blockchain — a distributed server infrastructure for executing code securely under consensus in a low trust environment. One of the applications of this technology is digital currencies. This is a textbook example where the cost of error is literally high. We naturally want its implementation to be as bulletproof as possible.

There are other cases though, even when not dealing with currencies, where bulletproof code makes sense. The cost of maintenance skyrockets quickly for a codebase that fails frequently. Being able to identify problems earlier in the development cycle, when the cost of fixing them is still low, has a good chance of paying back the upfront investment in a bulletproof methodology.

Is TDD the magic answer? Test Driven Development (TDD) is often hailed as the silver bullet against malfunctioning code. It is a puristic development methodology where new code isn’t added unless it satisfies a failing test. This process guarantees test coverage of 100 percent and often gives the illusion that your code is tested against every possible scenario.

This isn’t the case. TDD is a great methodology that works well for some, but by itself it still isn’t enough. Even worse, TDD instills false confidence in code and may make developers lazy when considering paranoid edge cases. I’ll show a good example of this later on.

Tests are important — they are the key It doesn’t matter if you write tests before the fact or after, using a technique like TDD or not. All that matters is that you have tests. Tests are the best line of defense for protecting your code against breaking in production.

Since we’re going to run our entire test suite very frequently — after every new line of code if possible — tests must be automated. No part of our confidence in our code can result from a manual QA process. Humans make mistakes. Human attention to detail deteriorates after doing the same mind-numbing task a hundred times in a row.

Tests must be fast. Blazingly fast.

If a test suite takes more than a few seconds to run, developers are likely going to become lazy, pushing code without running it. This is one of the great things about Go — it has one of the fastest toolchains out there. It compiles, rebuilds, and tests in seconds.

Tests are also important enablers for open-source projects. Blockchains, for example, are almost religiously open-source. The codebase must be open to establish trust — expose itself for audit and create a decentralized atmosphere where no single governing entity controls the project.

It is unreasonable to expect massive external contributions in an open-source project without a thorough test suite. External contributors need a quick way to check if their contribution breaks any existing behavior. The entire test suite, in fact, must run automatically on every pull request and fail automatically if the PR broke anything.

Full test coverage is a misleading metric, but it is important. It may feel excessive to reach 100% coverage, but when you think about it, it makes no sense to ship code to production that was never executed beforehand.

Full test coverage doesn’t necessarily mean that we have enough tests and it doesn’t mean that our tests are meaningful. What is certain is that if we don’t have 100% coverage, we don’t have enough to consider ourselves bulletproof, since parts of our code were never tested.

Nevertheless, there is such a thing as too many tests. Ideally, every bug we encounter should break a single test. If we have redundant tests — different tests that check the same thing — modifying existing code and breaking existing behavior in the process will incur too much overhead in fixing failed tests.

Why is Go a great choice for bulletproof code? Go is statically typed. Types provide a contract between various pieces of code running together. Without automatic type checking during build, if we wanted to adhere to our strict coverage rules, we would have to implement these contract tests ourselves. This is the case with environments like Node.js and JavaScript. Writing comprehensive contract tests manually is a lot of extra work we prefer to avoid.

Go is simple and dogmatic. Go is known for being stripped of many traditional language features like classic OOP inheritance. Complexity is the worst enemy of bulletproof code. Problems tend to creep up in the seams. While the common case is easy to test, it’s the strange edge case you haven’t thought of that will eventually get you.

Dogma is also helpful in this sense. There’s often only one way to do something in Go. This may inhibit the free spirit of man, but when there’s one way to do something, it’s more difficult to get this one thing wrong.

Go is concise yet expressive. Readable code is easier to review and audit. If the code is too verbose, its core purpose may be drowned by the noise of boilerplate. If the code is too concise, it becomes hard to follow and understand.

Go strikes a nice balance between the two. There’s not a lot of language boilerplate like in Java or C++, but the language is still very explicit and verbose in areas like error handling — making it easy to verify that you’ve checked every possible route.

Go has clear paths of error and recovery. Dealing gracefully with errors in runtime is a cornerstone for bulletproof code. Go has a strict convention of how errors are returned and propagated. Environments like Node.js — where multiple flavors of control flow like callbacks, promises, and async are mixed together — often result in leakage like unhandled promise rejections. Recovering from these is almost impossible.

Go has an extensive standard library. Dependencies add risk, especially when coming from sources that aren’t necessarily well-maintained. When shipping your server, you ship all of your dependencies with it. You are responsible for their malfunctions as well. Environments overflowing with fragmented dependencies, like Node.js, are harder to keep bulletproof.

This is also risky from a security standpoint, as you are as vulnerable as your weakest dependency. Go’s extensive standard library is well-maintained and reduces reliance on external dependencies.

Development velocity is still rapid. The main appeal of environments like Node.js is an extremely rapid development cycle. Code just takes less time to write and you become more productive.

Go preserves these benefits quite well. The build toolchain is fast enough to make feedback immediate. Compilation time is negligible, and code seems to run like it’s interpreted. The language has enough abstractions like garbage collection to focus engineering efforts on core functionality.

Let’s play with a working example Now, with the introductions over, it’s time to dive into some code. We need an example that is simple enough so we can focus on methodology, but complicated enough to have substance. I find it’s easiest to take something from my day to day, so let’s build a server that processes currency-like transactions. Users will be able to check the balance for an account. Users will also be able to transfer funds from one account to another.

We’ll keep things very simple. Our system will only have a single server. We’re also not going to deal with user authentication or cryptography. These are product features, whereas we want to focus on building the bulletproof software foundation.

Breaking down complexity to manageable parts Complexity is the worst enemy of bulletproof code. One of the best ways to deal with complexity is divide and conquer — split the problem into smaller problems and solve each one separately. How do we split? We’ll follow the principle of separation of concerns. Every part should deal with a single concern.

This goes hand in hand with the popular architecture of microservices. Our server will be comprised of services. Each service will be mandated a clear responsibility and given a well defined interface for communication with the other services.

Once we’ve structured our server this way, we’ll be free to decide how each service is running. We can run all services together in the same process, make each service its own separate server and communicate via RPC, or split services to run on different machines.

Since we’re just starting out, we’ll keep things simple — all services will share the same process and communicate directly as libraries. We’ll be able to change this decision easily in the future.

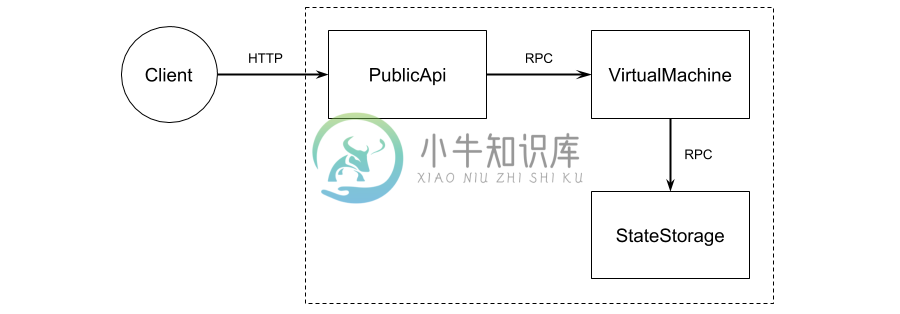

So which services should we have? Our server is a little too simple for splitting up, but to demonstrate this principle we’ll do so anyways. We need to respond to HTTP requests from clients for checking balances and making transactions. One service can deal with the client HTTP interface — we’ll call it PublicApi. Another service will own the state — the ledger of all balances —so we’ll call it StateStorage. The third service will connect the two and implement our business logic of the “contract” for changing balances. Since blockchains usually allow these contracts to be deployed by application developers, the third service will be charged with running them — we’ll call it VirtualMachine.

We’ll place the code for services in our project under /services/publicapi, /services/virtualmachine and /services/statestorage.

Defining service boundaries clearly When implementing services, we’ll want to be able to work on each one separately. Possibly even assign different services to different developers. Since services are dependent on one another and we’re going to parallelize work on their implementation, we’ll have to start by defining clear interfaces between them. Using this interface, we’ll be able to test a service individually and mock everything else.

How can we define the interface? One option is to document it, but documentation tends to grow stale and out of sync with the code. We could use Go interface declarations. This makes sense, but it’s nicer to define the interface in a language agnostic way. Our server isn’t limited to Go only. We may decide down the road to reimplement one of the services in a different language more appropriate to its requirements.

One approach is to use protobuf — a simple language-agnostic syntax by Google to define messages and service endpoints.

Let’s start with StateStorage. We’ll structure state as a key-value store:

syntax = "proto3";

package statestorage;

service StateStorage {

rpc WriteKey (WriteKeyInput) returns (WriteKeyOutput);

rpc ReadKey (ReadKeyInput) returns (ReadKeyOutput);

}

message WriteKeyInput {

string key = 1;

int32 value = 2;

}

message WriteKeyOutput {

}

message ReadKeyInput {

string key = 1;

}

message ReadKeyOutput {

int32 value = 1;

}

Although PublicApi is accessed via client HTTP, it’s still a good practice to give it a clear interface in the same way:

syntax = "proto3";

package publicapi;

import "protocol/transactions.proto";

service PublicApi {

rpc Transfer (TransferInput) returns (TransferOutput);

rpc GetBalance (GetBalanceInput) returns (GetBalanceOutput);

}

message TransferInput {

protocol.Transaction transaction = 1;

}

message TransferOutput {

string success = 1;

int32 result = 2;

}

message GetBalanceInput {

protocol.Address from = 1;

}

message GetBalanceOutput {

string success = 1;

int32 result = 2;

}

This will require us to define Transaction and Address data structures:

syntax = "proto3";

package protocol;

message Address {

string username = 1;

}

message Transaction {

Address from = 1;

Address to = 2;

int32 amount = 3;

}

We’ll place the .proto definitions for services in our project under /types/services and general data structures under /types/protocol. Once the definitions are ready, they can be compiled to Go code. The benefit of this approach is that code which doesn’t meet the contract will simply not compile. Alternate methods would require us to write contract tests explicitly.

The complete definitions, generated Go files, and compilation instructions are available here. Kudos to Square Engineering for making goprotowrap.

Note that we’re not integrating an RPC transport layer yet, and calls between services will currently be regular library calls. When we’re ready to split services to different servers, we can add a transport layer like gRPC.

The types of tests in our project Since tests are the key to bulletproof code, let’s discuss first which types of tests we’ll be writing:

Unit tests This is the base of the testing pyramid. We’ll test every unit in isolation. What’s a unit? In Go, we can define a unit to be every file in a package. If we have /services/publicapi/handlers.go, we’ll place its unit test in the same package under /services/publicapi/handlers_test.go.

It’s preferable to place unit tests in the same package as the tested code so the tests have access to non-exported variables and functions.

Service / integration / component tests The next type of tests has multiple names that all refer to the same thing — taking several units and testing them together. This is one level up the pyramid. In our case, we’ll focus on an entire service. These tests define the specifications for a service. For the StateStorage service for example, we’ll place them in /services/statestorage/spec.

It’s preferable to place these tests in a different package than the tested code to enforce access through exported interfaces only.

End-to-end tests This is the top of the testing pyramid, where we test our entire system together with all services combined. These tests define the end-to-end specifications for the system, therefore we’ll place them in our project under /e2e/spec.

These tests as well should be placed in a different package than the tested code to enforce access through exported interfaces only.

Which tests should we write first? Do we start at the base and work our way up? Or go top-down? Both approaches are valid. The benefit of the top-down approach is for building specifications. It’s usually easier to reason about the specifications for the entire system first. Even if we split our system to services the wrong way, the system spec would remain the same. This would also help us understand that.

The drawback of starting top-down is that our end-to-end tests will be the last ones to pass (only after the entire system has been implemented). This means they’ll remain failing for a long time.

End-to-end tests Before writing tests, we need to consider whether we’re going to write everything bare-boned or use a framework. Relying on frameworks for dev dependencies is less dangerous than relying on frameworks for production code. In our case, since the Go standard library doesn’t have great support for BDD and this format is excellent for defining specs, we’ll opt for a framework.

There are many excellent candidates like GoConvey and Ginkgo. My personal preference is Ginkgo with Gomega (terrible names, but what can you do) which use syntax like Describe() and It().

So what does a test look like? Checking user balance:

package spec

import ...

var _ = Describe("Sanity", func() {

var (

node services.Node

)

BeforeEach(func() {

node = services.NewNode()

node.Start()

})

AfterEach(func() {

node.Stop()

})

It("should show balances with GET /api/balance", func() {

resp, err := http.Get("http://localhost:8080/api/balance?from=user1")

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Expect(resp.StatusCode).To(Equal(http.StatusOK))

Expect(ResponseBodyAsString(resp)).To(Equal("0"))

})

})

Since our server provides public HTTP interface to the world, we access this web API using http.Get. What about making a transaction?

It("should transfer funds with POST /api/transfer", func() {

resp, err := http.Get("http://localhost:8080/api/transfer?from=user1&to=user2&amount=17")

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Expect(resp.StatusCode).To(Equal(http.StatusOK))

Expect(ResponseBodyAsString(resp)).To(Equal("-17"))

resp, err = http.Post("http://localhost:8080/api/balance?from=user2", "text/plain", nil)

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Expect(resp.StatusCode).To(Equal(http.StatusOK))

Expect(ResponseBodyAsString(resp)).To(Equal("17"))

})

The test is very descriptive and can even replace documentation. As you can see above, we’re allowing accounts to reach a negative balance. This is a product choice. If this weren’t allowed, the test would reflect that.

The complete test file is available here.

Service integration / component tests Now that we’re done with end-to-end tests, we go down the pyramid and implement service tests. This is done for every service separately. Let’s choose a service which has a dependency on another service, because this case is more interesting.

We’ll start with VirtualMachine. The protobuf interface for this service is available here. Because VirtualMachine relies on service StateStorage and makes calls to it, we’re going to have to mock StateStorage in order to test VirtualMachine in isolation. The mock object will allow us to control StateStorage’s responses during the test.

How can we implement mock objects in Go? We can simply create a bare-boned stub implementation, but using a mocking library will also provide us with useful assertions during the test. My preference is go-mock.

We’ll place the mock for StateStorage in /services/statestorage/mock.go. It’s preferable to place mocks in the same package as the mocked code to provide access to non-exported variables and functions. The mock is pretty much just boilerplate at this point, but as our services get more complicated, we may find ourselves adding some logic here. This is the mock:

If you assign different services to different developers, it makes sense to implement the mocks first and share them between the team.

Let’s get back to writing our service test for VirtualMachine. Which scenario should we test here exactly? It’s best to follow the interface for the service and design tests for each endpoint. We’ll implement the test for the endpoint CallContract() with the method argument of "GetBalance" first:

package spec

import ...

var _ = Describe("Contracts", func() {

var (

service uut.Service

stateStorage *_statestorage.MockService

)

BeforeEach(func() {

service = uut.NewService()

stateStorage = &_statestorage.MockService{}

service.Start(stateStorage)

})

AfterEach(func() {

service.Stop()

})

It("should support 'GetBalance' contract method", func() {

stateStorage.When("ReadKey", &statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: "user1"}).Return(&statestorage.ReadKeyOutput{Value: 100}, nil).Times(1)

addr := protocol.Address{Username: "user1"}

out, err := service.CallContract(&virtualmachine.CallContractInput{Method: "GetBalance", Arg: &addr})

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Expect(out.Result).To(BeEquivalentTo(100))

Expect(stateStorage).To(ExecuteAsPlanned())

})

})

Notice that the service we’re testing, VirtualMachine, receives a pointer to its dependency StateStorage in its Start() method via simple dependency injection. That’s where we pass the mocked instance. Also notice on line 23 where we instruct the mock with how to respond when accessed. When its ReadKey method is called, it should return the value 100. We then verify that it indeed was called exactly once in line 28.

These tests become the specifications for the service. The full suite for service VirtualMachine is available here. The suites for the other services are available here and here.

Let’s implement a unit, finally Implementing the contract for method "GetBalance" is a bit too simple, so let’s move instead to the slightly more complicated implementation for method "Transfer”. The transfer contract needs to read the balances of both the sender and recipient, calculate their new balances, and write them back to state. The service integration test for it is very similar to the one we just implemented:

It("should support 'Transfer' transaction method", func() {

stateStorage.When("ReadKey", &statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: "user1"}).Return(&statestorage.ReadKeyOutput{Value: 100}, nil).Times(1)

stateStorage.When("ReadKey", &statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: "user2"}).Return(&statestorage.ReadKeyOutput{Value: 50}, nil).Times(1)

stateStorage.When("WriteKey", &statestorage.WriteKeyInput{Key: "user1", Value: 90}).Return(&statestorage.WriteKeyOutput{}, nil).Times(1)

stateStorage.When("WriteKey", &statestorage.WriteKeyInput{Key: "user2", Value: 60}).Return(&statestorage.WriteKeyOutput{}, nil).Times(1)

t := protocol.Transaction{From: &protocol.Address{Username: "user1"}, To: &protocol.Address{Username: "user2"}, Amount: 10}

out, err := service.ProcessTransaction(&virtualmachine.ProcessTransactionInput{Method: "Transfer", Arg: &t})

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Expect(out.Result).To(BeEquivalentTo(90))

Expect(stateStorage).To(ExecuteAsPlanned())

})

We’ll finally get down to business and create a unit called processor.go that contains the actual implementation for the contract. This is what our initial implementation turns out:

package virtualmachine

import ...

func (s *service) processTransfer(fromUsername string, toUsername string, amount int32) (int32, error) {

fromBalance, err := s.stateStorage.ReadKey(&statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: fromUsername})

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

toBalance, err := s.stateStorage.ReadKey(&statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: toUsername})

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

_, err = s.stateStorage.WriteKey(&statestorage.WriteKeyInput{Key: fromUsername, Value: fromBalance.Value - amount})

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

_, err = s.stateStorage.WriteKey(&statestorage.WriteKeyInput{Key: toUsername, Value: toBalance.Value + amount})

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

return fromBalance.Value - amount, nil

}

This satisfies the service integration test, but the integration test only contains a common case scenario. What about edge cases and potential failures? As you can see, any of the calls we make to StateStorage may fail. If we’re aiming for 100-percent coverage, we need to check all of these cases. A unit test would be a great place to do that.

Since we’re going to have to run the function multiple times with different inputs and mock settings to reach all flows, a table driven test would make this process a little more efficient. The convention in Go is to avoid fancy frameworks in unit tests. We can drop Ginkgo, but we should probably keep Gomega so our matchers look similar to our previous tests. This is the test:

package virtualmachine

import ...

var transferTable = []struct{

to string // the username we transfer to

read1Err error // does the first read fail with error

read2Err error // does the second read fail with error

write1Err error // does the first write fail with error

write2Err error // does the second write fail with error

output int32 // the output we expect

errs bool // do we expect the function to return an error

}{

{"user2", errors.New("a"), nil, nil, nil, 0, true},

{"user2", nil, errors.New("a"), nil, nil, 0, true},

{"user2", nil, nil, errors.New("a"), nil, 0, true},

{"user2", nil, nil, nil, errors.New("a"), 0, true},

{"user2", nil, nil, nil, nil, 90, false},

}

func TestTransfer(t *testing.T) {

Ω := NewGomegaWithT(t)

for _, tt := range transferTable {

s := NewService()

ss := &_statestorage.MockService{}

s.Start(ss)

ss.When("ReadKey", &statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: "user1"}).Return(&statestorage.ReadKeyOutput{Value: 100}, tt.read1Err)

ss.When("ReadKey", &statestorage.ReadKeyInput{Key: "user2"}).Return(&statestorage.ReadKeyOutput{Value: 50}, tt.read2Err)

ss.When("WriteKey", &statestorage.WriteKeyInput{Key: "user1", Value: 90}).Return(&statestorage.WriteKeyOutput{}, tt.write1Err)

ss.When("WriteKey", &statestorage.WriteKeyInput{Key: "user2", Value: 60}).Return(&statestorage.WriteKeyOutput{}, tt.write2Err)

output, err := s.(*service).processTransfer("user1", tt.to, 10)

if tt.errs {

Ω.Expect(err).To(HaveOccurred())

} else {

Ω.Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Ω.Expect(output).To(BeEquivalentTo(tt.output))

}

}

}

If you’re weirded out by the “Ω” symbol don’t worry, it’s just a regular variable name (holding a pointer to Gomega). You’re welcome to rename it to anything you like.

For the sake of time, we didn’t show the strict methodology of TDD where a new line of code would only be written to resolve a failing test. Using this methodology, the unit test and implementation for processTransfer() would be implemented over several iterations.

The full suite of unit tests in the VirtualMachine service is available here. The unit tests for the other services are available here and here.

We’ve reached 100% coverage, our end-to-end tests are passing, our service integration tests are passing and our unit tests are passing. The code fulfills its requirements to the letter and is thoroughly tested.

Does that mean that everything is working? Unfortunately not. We still have several nasty bugs hiding in plain sight in our simple implementation.

The importance of stress tests All of our tests so far tested a single request being handled at any given time. What about synchronization issues? Every HTTP request in Go is handled in its own goroutine. Since these goroutines run concurrently, potentially on different OS threads on different CPU cores, we face synchronization problems. These are very nasty bugs that aren’t easy to track down.

One of the approaches for finding synchronization issues is stressing the system with many requests in parallel and making sure everything still works. This should be an end-to-end test because we want to test synchronization issues across our entire system with all services. We’ll place stress tests in our project under /e2e/stress.

This is what a stress test looks like:

package stress

import ...

const NUM_TRANSACTIONS = 20000

const NUM_USERS = 100

const TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH = 200

const BATCHES_PER_SEC = 40

var _ = Describe("Transaction Stress Test", func() {

var (

node services.Node

)

BeforeEach(func() {

node = services.NewNode()

node.Start()

})

AfterEach(func() {

node.Stop()

})

It("should handle lots and lots of transactions", func() {

// customize HTTP client to handle many connections

transport := http.Transport{

IdleConnTimeout: time.Second*20,

MaxIdleConns: TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH*10,

MaxIdleConnsPerHost: TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH*10,

}

client := &http.Client{Transport: &transport}

// create a local ledger for verification

ledger := map[string]int32{}

for i := 0; i < NUM_USERS; i++ {

ledger[fmt.Sprintf("user%d", i+1)] = 0

}

// send all transactions over HTTP in batches

rand.Seed(42)

done := make(chan error, TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH)

for i := 0; i < NUM_TRANSACTIONS / TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH; i++ {

log.Printf("Sending %d transactions... (batch %d out of %d)", TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH, i+1, NUM_TRANSACTIONS / TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH)

time.Sleep(time.Second / BATCHES_PER_SEC)

for j := 0; j < TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH; j++ {

from := randomizeUser()

to := randomizeUser()

amount := randomizeAmount()

ledger[from] -= amount

ledger[to] += amount

go sendTransaction(client, from, to, amount, &done)

}

for j := 0; j < TRANSACTIONS_PER_BATCH; j++ {

err := <- done

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

}

}

// verify the ledger

for i := 0; i < NUM_USERS; i++ {

user := fmt.Sprintf("user%d", i+1)

resp, err := client.Get(fmt.Sprintf("http://localhost:8080/api/balance?from=%s", user))

Expect(err).ToNot(HaveOccurred())

Expect(resp.StatusCode).To(Equal(http.StatusOK))

Expect(ResponseBodyAsString(resp)).To(Equal(fmt.Sprintf("%d", ledger[user])))

}

})

})

func randomizeUser() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("user%d", rand.Intn(NUM_USERS)+1)

}

func randomizeAmount() int32 {

return rand.Int31n(1000)+1

}

func sendTransaction(client *http.Client, from string, to string, amount int32, done *chan error) {

url := fmt.Sprintf("http://localhost:8080/api/transfer?from=%s&to=%s&amount=%d", from, to, amount)

resp, err := client.Post(url, "text/plain", nil)

if err == nil {

ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

resp.Body.Close()

}

*done <- err

}

Notice that the stress test includes random data. It’s recommended to use a constant seed (see line 39) to make the test deterministic. Running a different scenario every time we run our tests isn’t a good idea. Flakiness by tests that sometimes pass and sometimes fail reduces developer confidence in the suite.

The tricky part about stress tests over HTTP is that most machines have a hard time simulating thousands of concurrent users and opening thousands of concurrent TCP connections (you’ll see strange failures like “maximum file descriptors” or “connection reset by peer”). The code above tries to deal with this gracefully by limiting concurrent connections to batches of 200 and using IdleConnection Transport settings to recycle TCP sessions between batches. If this test is flaky on your machine, try reducing the batch size to 100.

Oh no…the test fails:

fatal error: concurrent map writes

goroutine 539 [running]:

runtime.throw(0x147bf60, 0x15)

/usr/local/go/src/runtime/panic.go:616 +0x81 fp=0xc4207159d8 sp=0xc4207159b8 pc=0x102ca01

runtime.mapassign_faststr(0x13f5140, 0xc4201ca0c0, 0xc4203a8097, 0x6, 0x1012001)

/usr/local/go/src/runtime/hashmap_fast.go:703 +0x3e9 fp=0xc420715a48 sp=0xc4207159d8 pc=0x100d879

services/statestorage.(*service).WriteKey(0xc42000c060, 0xc4209e6800, 0xc4206491a0, 0x0, 0x0)

services/statestorage/methods.go:15 +0x10c fp=0xc420715a88 sp=0xc420715a48 pc=0x138339c

services/virtualmachine.(*service).processTransfer(0xc4201ca090, 0xc4203a8097, 0x6, 0xc4203a80a1, 0x6, 0x2a4, 0xc420715b30, 0x1012928, 0x40)

services/virtualmachine/processor.go:19 +0x16e fp=0xc420715ad0 sp=0xc420715a88 pc=0x13840ee

services/virtualmachine.(*service).ProcessTransaction(0xc4201ca090, 0xc4209e67c0, 0x30, 0x1433660, 0x12a1d01)

Ginkgo ran 1 suite in 1.288879763s

Test Suite Failed

What happens here? StateStorage is implemented as simple in-memory map. It seems we’re trying to write to this map in parallel from different threads. It may seem at first that we should just replace the regular map with the thread-safe sync.map but our problem runs a little deeper.

Take a look at the processTransfer() implementation. It reads twice from the state and then writes twice. The set of reads and writes isn’t an atomic transaction, so if another thread changes the state after one thread read from it, we’re going to have data corruption. The fix is to make sure only one instance of processTransfer() can run concurrently — you can see it here.

Let’s try to run the stress test again. Oh no, another failure!

e2e/stress/transactions.go:44

Expected

<string>: -7498

to equal

<string>: -7551

e2e/stress/transactions.go:82

------------------------------

Ginkgo ran 1 suite in 5.251593179s

Test Suite Failed

This one requires a little more debugging to understand. It seems that it happens when a user tries to transfer an amount to themselves (the same user is both the sender and recipient). Looking at the implementation, it’s easy to see why this happens.

This one is a little disturbing. We’ve followed a TDD-like workflow and we still hit a hard business logic bug. How can that be? Isn’t our code tested against every scenario with 100% coverage?! Well…this bug is the result of a faulty product requirement, not a faulty implementation. The requirements for processTransfer() should have clearly stated that if a user transfers an amount to themselves, nothing happens.

When we discover a business logic bug, we should always reproduce it first in our unit tests. It’s very easy to add this case to our table driven test from before. The fix is also simple — you can see it here.

Are we finally home free? After adding the stress tests and making sure everything passes, is our system finally working as intended? Is it finally bulletproof?

Unfortunately not.

We still have some nasty bugs that even the stress test did not uncover. Our “simple” function processTransfer() is still at risk. Consider what happens if we ever reach this line. The first write to state succeeded but the second fails. We’re about to return an error, but we’ve already corrupted our state by writing to it half-baked data. If we’re going to return an error, we’ll have to undo the first write.

This is a little more complicated to fix. The best solution is probably to change our interface altogether. Instead of having an endpoint in StateStorage named WriteKey that we call twice, we should probably rename it to WriteKeys — an endpoint that we’ll call once to write both keys together in one transaction.

There’s a bigger lesson here: a methodical test suite is not enough. Dealing with complex bugs requires critical thinking and paranoid creativity by developers. It’s recommended to have someone else look at your code and perform code reviews in your team. Even better, open sourcing your code and encouraging the community to audit it is one of the best ways to make your code more bulletproof.